9. The Church in the underground 1946–1989

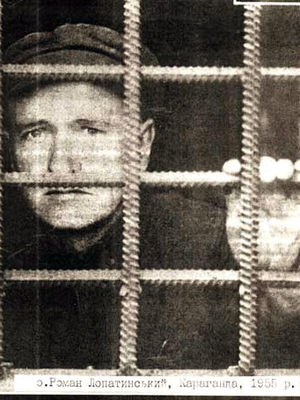

Father Roman Lopatyns’ky. Karaganda, 1955

Any pastoral work done by Greek-Catholic priests after the Lviv pseudo-council was considered illegal by the authorities, and priests, monks and nuns were repressed. In particular, on charges of “counter-revolutionary activities” and “high treason” Metropolitan Josyf Slipy was sentenced to eight years in labor camps and three years of deprivation of civil rights. Bishop Nykyta Budka was sentenced to five years in prison and three years of deprivation of civil rights, Bishop Nicholas Charnetsky — to five years in prison and three years of deprivation of civil rights, and Bishop Ivan Lyatyshevsky — to ten years. Bishop Gregory Khomyshyn died in a Kyiv prison on December 28, 1945 before the judicial process began. Przemysl Bishop Josaphat Kotsylovsky died in the Chapaivka-Vita camp outside Kyiv on December 17, 1947. Vicar General of the Lviv Archeparchy Bishop Nykyta Budka died in exile in Karaganda (Kazakhstan) on October 1, 1949. On November 12, 1950, Auxiliary Bishop of Peremysl Hryhory Lakota died in exile near Vorkuta.

Father Roman Lopatyns’ky. Karaganda, 1955

Any pastoral work done by Greek-Catholic priests after the Lviv pseudo-council was considered illegal by the authorities, and priests, monks and nuns were repressed. In particular, on charges of “counter-revolutionary activities” and “high treason” Metropolitan Josyf Slipy was sentenced to eight years in labor camps and three years of deprivation of civil rights. Bishop Nykyta Budka was sentenced to five years in prison and three years of deprivation of civil rights, Bishop Nicholas Charnetsky — to five years in prison and three years of deprivation of civil rights, and Bishop Ivan Lyatyshevsky — to ten years. Bishop Gregory Khomyshyn died in a Kyiv prison on December 28, 1945 before the judicial process began. Przemysl Bishop Josaphat Kotsylovsky died in the Chapaivka-Vita camp outside Kyiv on December 17, 1947. Vicar General of the Lviv Archeparchy Bishop Nykyta Budka died in exile in Karaganda (Kazakhstan) on October 1, 1949. On November 12, 1950, Auxiliary Bishop of Peremysl Hryhory Lakota died in exile near Vorkuta.

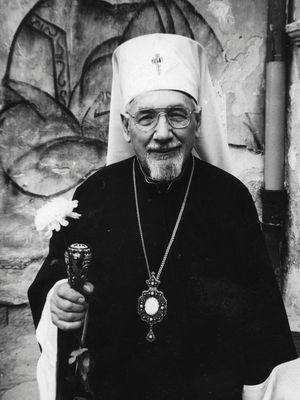

Even though the “visible” Church structure was destroyed by the arrests of its bishops, the UGCC succeeded in keeping the continuity of episcopal ministry in the conditions of persecution and deep underground. Episcopal ordinations were carried out in strict secrecy by the underground bishops.

From 1945 to 1989, fifteen underground bishops were ordained in secrecy.

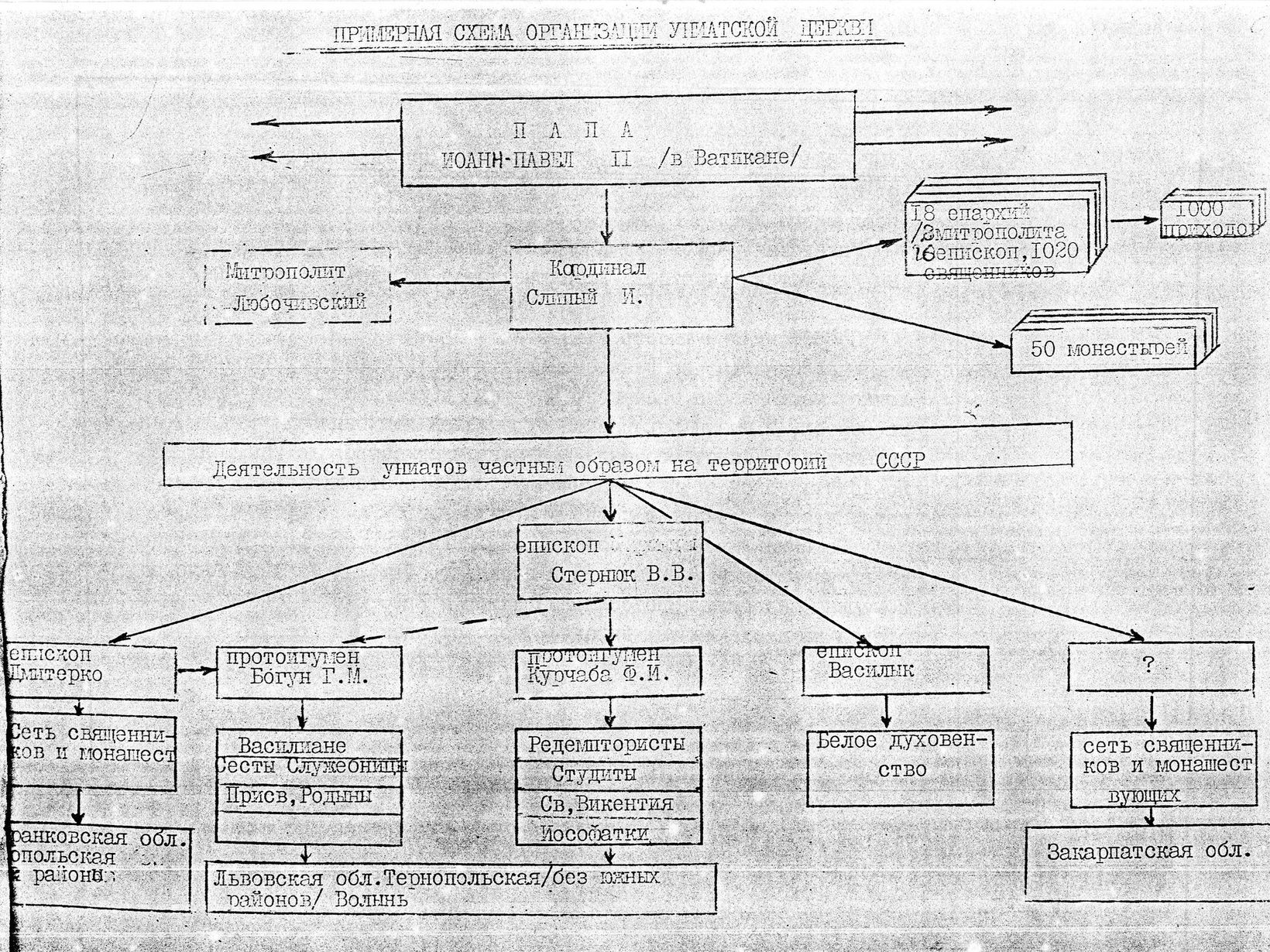

In 1945–1946 alone the KGB arrested and convicted more than 800 Greek-Catholic priests, who received prison terms from 10 to 25 years. The geography of the imprisoned clergy, monks and laity was vast: Mordovska ARSR (Dubrovlag), Komi ARSR (Vorkutlag, Rechlag, Intlag, Minlag) Kazakhstan (Karlag, Steplah), Siberia (Norillag, Ozerlag), the Far East (Berlag, Kolymlag), and other places.

After serving their prison terms, they were exiled to such faraway places as Krasnoyarsk, Chita Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai. The atheistic authorities failed, however, to break the true spirit of resistance. Despite the unbearable physical and mental conditions in the Soviet camps and harsh conditions in exile, the Greek-Catholic clergy used every opportunity to fulfill their pastoral vocation. In prisons and in exile they held liturgies, prayers, and administered Holy Sacraments. The priests baptized children in “special settlements,” officiated wedding ceremonies, and not only for Ukrainians. Even priestly ordinations were held in the labor camps.

In Galicia, church life continued in hiding, including with the help of those bishops, priests, monks, and faithful who returned from the camps and exile. Secret worship services would take place in private homes, places of pilgrimage, and in front of the closed churches. Underground liturgies were held mainly at night behind closed doors and windows with curtains drawn. The number of faithful attending these Divine Services numbered from a few individuals to several dozen. The Liturgy was usually preceded by Confession. The priest in most cases would wear just an orarion, which was easy to hide in case of a police raid. For security reasons, priests did not always use church utensils.

After the dissolution of monasteries and arrests, hegumens, monks and nuns would live in small communities of 3–4 persons and perform the duties prescribed by ordinance. Monastic congregations were replenished with young people who came on the recommendations of sisters or priests.

Nuns helped in the religious education of children, kept the Holy Eucharist at their homes, agreed on the place and time of worship, especially on Christmas and Easter, and brought everything needed for the service. In such “traveling churches” sisters worked as sextons, deacons, and catechists, the teachers of God’s law. Lay people extended considerable support to underground priests and bishops. Their homes often become places of worship and the administration of sacraments.

The Church faithful paid considerable attention to Christian parenting, manufactured and stored liturgical utensils, took care of closed churches, accompanied and guarded their pastors, brought priests to people who needed confession or communion, and hence rightly become indestructible pillars of the underground Church.

One of the biggest challenges of underground church leaders was recruiting candidates for the clergy as well as their training and ordination. To this end, secret seminaries were created, in which a new generation of clergy was educated, thus ensuring the continuity of the Church’s pastoral ministry.